How is the Unified Patent Court shaping up for biotech?

In this blog, Will James and Robyn Trigg from Osborne Clarke look at how the Unified Patent Court (UPC) practice and procedure has developed since it began operations in June 2023.

After decades of effort to introduce a single European forum for patent litigation, the Unified Patent Court (UPC) finally opened its doors on 1 June 2023. Since then, the court has proved to be a popular venue, with its caseload continuing to increase and the number of Unitary Patent (UP) applications and registrations also increasing.

There are currently 18 EU member states participating in the UPC, including Germany, Italy, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Sweden. We are currently in the 7-year transition period (which may or may not be extended for a further 7 years), during which the UPC does not have exclusive jurisdiction over European Patents (EPs). Proceedings relating to EPs can be brought either in the UPC or in the national courts throughout the transition period. Patentees can still opt-out their EPs from the UPC system during the transition period. However, UPs can only be litigated in the UPC.

A total of 635 cases have been commenced in the UPC (up until the end of December 2024). The total number of cases has been steadily increasing over the last months, with 50 new cases being started in the Court of First Instance in December 2024 alone.

The Court of Appeal's activity is also increasing – naturally, with more substantive decisions, there is an increase in the number of appeals. There were 10 new appeals in December 2024 alone.

English is the dominant language of proceedings.

Trends

Although the practice and procedure of the UPC are still developing, a number of important trends and issues have emerged from the decisions so far.

Court users

Prior to the start of the UPC, life sciences businesses were predicted to take a cautious approach to the court to see how its jurisprudence developed. However, we have seen a number of life sciences cases being commenced, notably the first case brought in the UPC. Medtech disputes have dominated, although we have also seen disputes concerning diagnostics, and the more usual innovator vs. innovator and innovator vs. generics biosimilar pharmaceutical disputes.

Timings

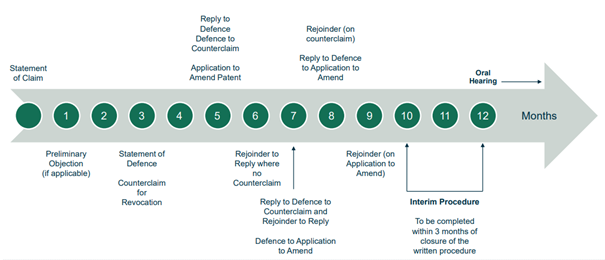

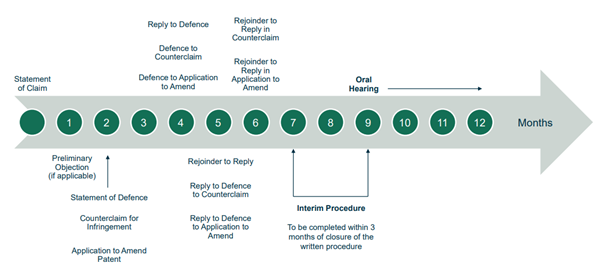

The Rules of Procedure set out strict timelines for each stage of the litigation. The UPC has so far proved that it can meet its timeline of providing first instance decisions on the merits in approximately one year from the start of the proceedings.

To stay on track to meet the one-year timeline, the court has been sticking closely to the prescribed deadlines, with only some very short extensions of time – for example, in a complex standard essential patent case where the complexity justified a short extension – but many rejections of extension requests.

Infringement first (at Local Division)

Revocation first (at Central Division)

Substantive decisions

-

Preliminary injunctions

There have been a number of both inter partes and ex parte preliminary injunction applications, including appeals to the Court of Appeal.

The most notable of these cases was the first preliminary injunction application made on the court's opening day in 10x Genomics v Nanostring. A preliminary injunction was initially granted by the Court of First Instance but was overturned by the Court of Appeal in its first substantive decision.

At first instance, the Munich local division held that there was a "sufficient degree of certainty" that the patent at issue was valid. The court also balanced the parties' interests, finding that 10x Genomics' interest in not having its patent infringed outweighed the interests of Nanostring in securing a market share.

This decision was initially heralded as the UPC establishing itself as a patentee-friendly court. Despite the injunction being overturned by the Court of Appeal, the Munich local division's approach of conducting a detailed review of a patent's validity on a case-by-case basis has endured and been used as a blueprint in other cases.

In deciding to overturn the first instance court's decision, the Court of Appeal reassessed the decision on validity. The Court of Appeal took a different approach to claim construction. The Court of Appeal disagreed with the first instance court on one aspect of claim construction and therefore was not convinced that the validity of the patent had been shown to a sufficient degree of certainty to justify the preliminary injunction. (As an aside, the EPO's Opposition Division has recently upheld 10x Genomics' patent in a slightly amended form. Although this doesn’t mean that the injunction automatically enters into force again, it could mean a permanent injunction will be forthcoming in the future in the pending main proceedings before the Munich local division.)

Since this case, it has been fairly evenly balanced between whether the preliminary injunction has been granted or not.

-

Final injunctions

The first final injunction came from the UPC's first decision on the merits, relating to the infringement of a patent for a sanitation bathtub device. The issued injunction covered seven UPC Contracting Member States. The Düsseldorf local division took an EPO-style approach to claim construction, following the Court of Appeal's approach in 10x Genomics v Nanostring. The defendant had sought to argue that it had a defence of right of prior use but the information on prior use related to Germany, which was not included in the claim, so the defence was dismissed.

-

Decisions on the merits

The UPC can be seen to be quite patentee-friendly so far. Across the Court of First Instance's decisions, the majority of patents have been found valid, particularly through the use of auxiliary amendments. Indeed, the majority of patents found to be valid have also been found to be infringed.

The court has made it clear that it is developing its own methodology and is not simply following an EPO-style approach (as had been predicted by some before the court opened). However, we have seen national approaches in the different divisions having some influence. For example, we have typically seen evidence preservation (saisie) applications made in jurisdictions with a similar procedure in national law. This gives users of the court system scope to forum shop amongst the local divisions to use local approaches to their advantage. Forum shopping could be particularly useful in exploring the limits of the use and influence of experts and cross-examination, and more generally, the approach to the hearing.

Arguably, we have seen life sciences companies hold back their 'crown jewel' patents from the UPC system, instead trying out the new forum with weaker or less strategically relevant patents. The UPC is inherently high risk, high reward – where a patentee stands to obtain a pan-UPC injunction to take an infringer off the market in one single action or have their patent revoked in all those jurisdictions. However, if the UPC's jurisprudence continues to develop in a patentee-friendly manner, this is likely to change.

There are still many unknowns and numerous issues that the UPC has yet to address, or which have not been addressed by the Court of Appeal, so there is plenty of scope for court users to attempt to develop the case law favourably.